Monash Sensory Science ‘Highly Commended’ Award – Victorian Premier’s Design Awards

2023 Victorian Premier’s Design Awards Winners Announced

More innovative and creative designers from across Victoria have been celebrated for their achievements, with the Victorian Premier’s Design Award of the Year shining a light on the people who take Victoria’s design industry from strength to strength.

Minister for Creative Industries Colin Brooks today congratulated all the winners and finalists of the Victorian Premier’s Design Awards, which showcase the best of Victorian innovation and design from the past 12 months – backed by the Allan Labor Government.

This year’s award was won by UNESCO World Heritage listed Budj Bim Cultural Landscape, with the tourism infrastructure project featuring a Visitor Information Centre, café and boardwalks that pays homage to the area’s history as one of the world’s most extensive and oldest aquaculture systems.

Budj Bim Cultural Landscape – 2023 Victorian Premier’s Design Award of the Year

The design reflects the rich history of the Gunditjamara Traditional Owners who have worked and fished on the land for more than 30,000 years while the projects supports them to care for Country and share their stories with the growing number of visitors to the site which gained World Heritage status in 2019.

The project was commissioned by the Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Corporation and was designed by Hamilton architectural firm Cooper Scaife Architects.

Founded in 1996, the Government’s annual awards celebrate design across eight categories – architectural, communication, digital, product, fashion, service, student and design strategy, with this year’s winners chosen from more than 330 entries.

Other winners include the CYBERTONGUE Food Testing System, a tool that analyses food samples in minutes, and a The Social Studio, Kay Abude and Alpha60 collaboration which uses off-cuts to create zero-waste bags and hats.

Swinburne University product design graduate Lily Geyle took home the Student Design category award for a post-operation recovery device for transgender people, while the Service Design winner was One Stop One Story, an online information hub where users tell their story before being connected to multiple corporate and community services.

The Design Strategy award went to the Fashion Futuring Toolkit which helps fashion designers and students learn ways to combat climate change, while design agency AKQA won the Digital Design award for its Nike campaign which used AI and machine learning to create a live virtual tennis match between two versions of Serena Williams.

Design is an economic powerhouse of Victoria’s $38.4 billion creative industries sector, employing almost 200 000 people and injecting $6 billion annually into the state economy.

View All Winners and Finalists

View Monash Sensory Science entry

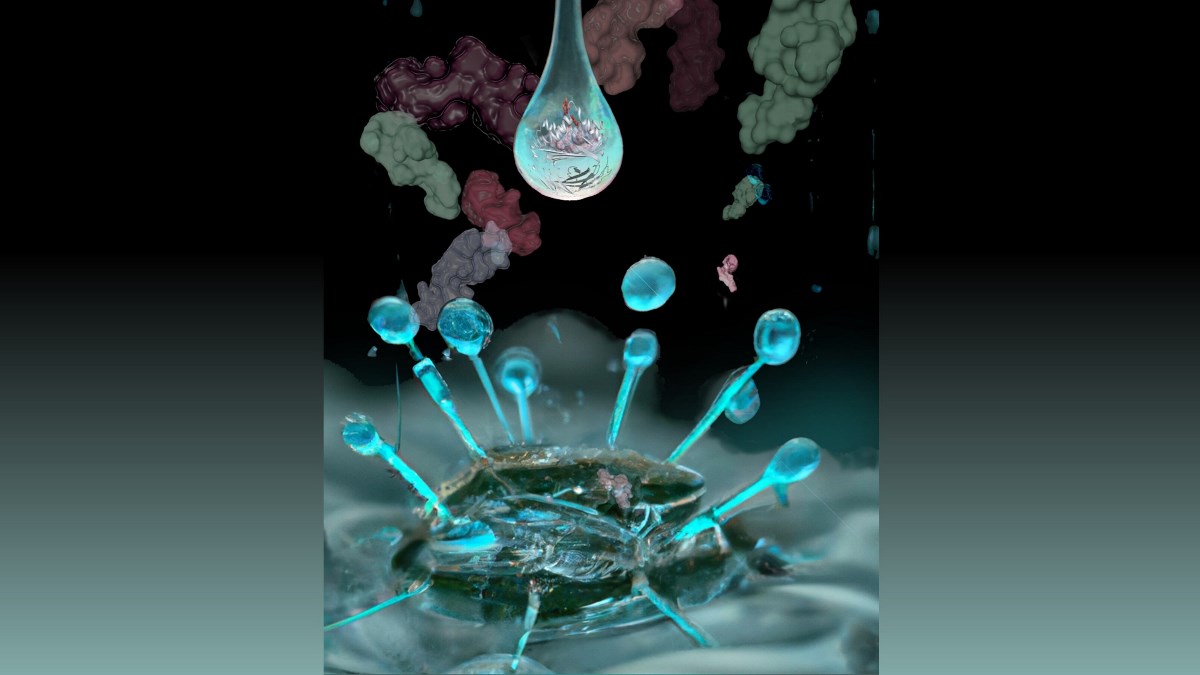

Monash Sensory Science is a world-first, multisensory design strategy engaging one of Australia’s leading biomedicine institutes through multisensory design, co-creation, STEM exhibition and outreach for blind, low vision and diverse-needs communities. Leveraging the lived experience of a legally blind artist/designer, the program has empowered scientists to communicate cutting edge biomedical discovery through creative multisensory exhibitions for diverse needs audiences. Together with Swinburne University designers, Monash Sensory Science enables diverse engagement, through visual and tactile design, novel technologies, interactions and experiences, audio design and sonification and through multisensory science books. The initiative has achieved national and international recognition

Quotes attributable to Minister for Creative Industries Colin Brooks

“The Victorian Premier’s Design Awards celebrate the incredible achievements of Victorian designers, whose innovations impact our everyday lives, from what we wear and how we communicate, to the buildings we inhabit.

“Congratulations to all finalists and winners who showcase the very best of our design industry, which supports thousands of jobs across the state and continues to produce world-leading innovations.”

Quotes attributable to Assoc. Prof. Leah Heiss Chair of the Victorian Premier’s Design Awards

“In my inaugural year as Chair of these prestigious awards, I have been truly inspired by the scope of innovation and the capacity for creativity demonstrated within the State. I want to congratulate all of the Finalists and Winners showcased through these awards, each project tells a unique design story, reflecting the vibrant and diverse culture here in Victoria.

The incredible talent represented in these awards clearly defines our State as a creative capital, and I am looking forward to seeing what is possible as our design community continues to push boundaries and strive for excell